China vs India: las claves para entender la larga disputa fronteriza que generó un enfrentamiento que dejó varios soldados muertos

India y China, los dos países más poblados del mundo, con dos enormes ejércitos y con armas nucleares, llevan semanas en desacuerdo en la región del Himalaya.

Pero la crisis escaló este martes. El Ejército indio dice que al menos 20 soldados fallecieron en un nuevo conflicto y que también hubo heridos en el lado chino.

China no confirmó ninguna victima hasta este martes.

Se trata de las primeras muertes desde hace más de cuatro décadas de conflicto sobre la disputada frontera entre los dos gigantes asiáticos.

Pero, ¿qué llevó a la actual situación y qué hay detrás de ello?

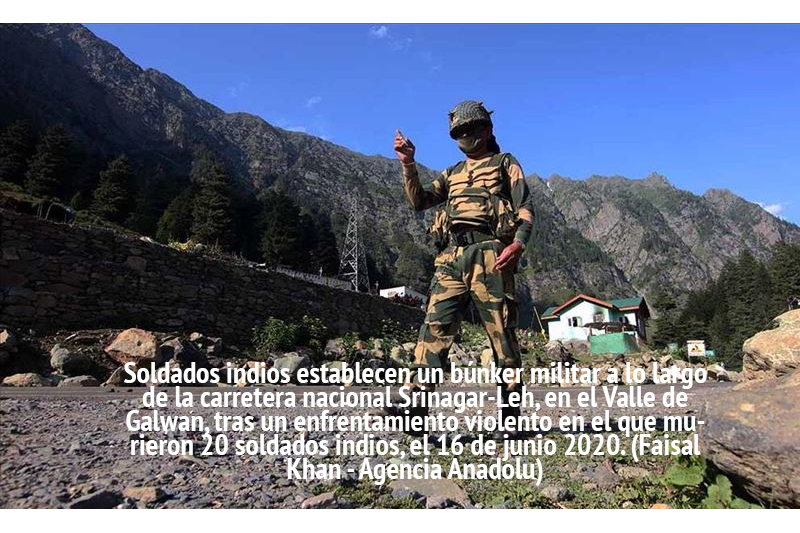

El lugar donde se produjo el último enfrentamiento se sitúa en la frontera de facto, llamada Línea de Control Actual (o LAC, por sus siglas en inglés), en concreto, en el valle de Galwan, en Ladakh.

Este valle se encuentra en la disputada región de Cachemira, altamente militarizada y frecuente fuente de conflicto por las soberanía territorial entre India, Pakistán y China.

En el valle de Galwan se han producido numerosos incidentes entre patrullas indias y chinas, y desde abril ambos lados han amasado tanques, artillería, lanzacohetes y tropas en las proximidades de esta zona.

Las fuerzas terrestres están respaldadas por helicópteros de ataque y aviones de combate.

A principios de mayo, las tensiones aumentaron después de que los medios indios informaran de que las fuerzas chinas habían instalado tiendas, trincheras y trasladado equipo pesado varios kilómetros adentro del territorio que India considera como propio.

La acción se produjo después de que India construyera una carretera de varios cientos de kilómetros para llegar a una base aérea en alta altitud que reactivó en 2008.

Tras este punto álgido de las tensiones, India ha culpado a China de la situación.

“Durante el proceso de desescalada [de las tensiones] en el valle de Galwan, un enfrentamiento violento se produjo ayer por la noche con víctimas en ambas lados”, señala un comunicado del Ejército indio este martes.

China, por su parte, pidió a India “no tomar acciones unilaterales o provocar problemas”.

El portavoz de la Cancillería china Zhao Lijian dijo que era India quien había cruzado la frontera, “provocando y atacando al personal chino, lo que resultó en una grave confrontación física entre las fuerzas fronterizas”.

¿Qué hay detrás de la disputa?

Varios factores llevan a esta confrontación, pero la raíz es la rivalidad entre ambos por sus objetivos estratégicos.

India y China comparten una frontera de más de 3.440 kilómetros y tienen reclamaciones territoriales superpuestas.

Desde los años 50, China se ha negado a reconocer las fronteras diseñadas durante la era colonial británica.

En 1962, eso llevó a una breve pero brutal guerra entre ambos países, que acabó con la humillante derrota militar de India.

Desde el conflicto bélico, las dos naciones asiáticas se han acusado mutuamente de ocupar su territorio.

India asegura que China está ocupando 38.000 kilómetros cuadrados de su territorio, que tiene que ver con el área donde ocurrió la actual confrontación.

China se atribuye la soberanía de todo el estado indio de Arunachal Pradesh, al que llama Tíbet del sur.

También hay otros sectores donde ambos países tienen diferentes visiones sobre dónde se sitúa la frontera.

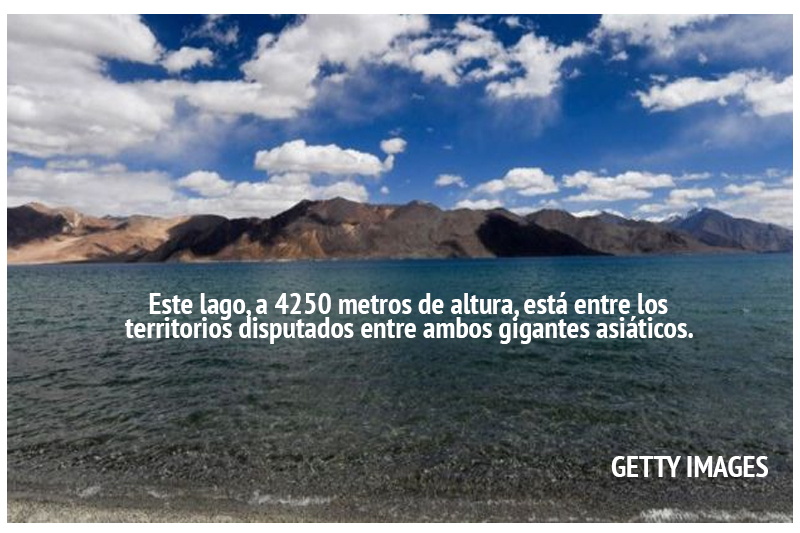

La LAC es en realidad una línea de demarcación muy ambigua, pues la presencia de ríos, lagos y montañas nevadas hace que esa frontera de facto varíe y a menudo genera confrontación.

Durante las últimas tres décadas, India y China han protagonizado diversas rondas de diálogo sobre disputas fronterizas que fracasaron en hallar una solución permanente, si bien mantuvieron cierta estabilidad en la región.

La construcción de infraestructura

Para apoyar a las tropas desplegadas en este terreno hostil e inhabitable, ambos lados han construido infraestructura, algo en lo que India ha estado tratando de ponerse al día.

Bajo el gobierno de Narendra Modi, India ha empezado a construir decenas de carreteras a lo largo de la LAC y se apresura para cumplir con su objetivo de completar estos proyectos para diciembre de 2022.

Una de esas vías da acceso al valle de Galwan, donde ocurrió el actual conflicto.

China también ha estado construyendo carreteras y otro tipo de infraestructura en esta zona de relevancia estratégica para Pekín, pues conecta la región occidental de Xinjiang y el occidente del Tíbet.

Poder global vs. poder regional

La economía china es casi cinco veces mayor que la de India y rivaliza en el campo estratégico global con la de Estados Unidos.

India, por otro lado, alberga visiones de un orden mundial multipolar, donde espera desempeñar un papel importante.

Los políticos y analistas indios en ocasiones hablan, no obstante, como si India y China fueran potencias similares, sin admitir los enormes avances de Pekín.

El pasado agosto, India decidió de forma controvertida acabar con la autonomía limitada de Jammy y Cachemira, y redibujar el mapa de la región, una decisión que fue denunciada por Pekín.

Ello creó la nueva regiónadministrativa Ladakh, que incluye Aksai Chin, un área que India reclama pero que controla China. Ahí es donde se produjo el enfrentamiento.

El factor Pakistán y el conflicto del Tíbet

India ha desconfiado de la relación entre China y Pakistán -aliados de larga data-, y ha acusado al primero de ayudar al último a adquirir tecnología nuclear y de misiles.

Veteranos líderes del gobierno nacionalista hindú BJP han estado hablando también de recuperar la parte de Cachemira administrada por Pakistán.

Una carretera estratégica, la autovía Karakoram, cruza esta área que conecta China con Pakistán.

Pekín ha invertido alrededor de US$60.000 millones en infraestructura pakistaní, como parte del llamado corredor económico China-Pakistán, que a su vez forma parte de la nueva Ruta de la Seda impulsada por el gobierno chino.

Esta autovía es clave para transportar bienes hacia y desde el puerto sureño de Gwadar de Pakistán. El puerto proporciona a China una entrada al Mar Arábigo.

India teme que en el futuro cercano Gwadar pueda ser usada para apoyar las operaciones navales de China en ese mar.

El Tíbet es otro punto de conflicto.

China recela de la relación entre el gobierno indio y el dalái lama, el líder espiritual tibetano que huyó a India tras el fallido levantamiento popular de 1959 en Tíbet.

India se ha negado a reconocer al gobierno tibetano en el exilio, pero su principal líder estuvo entre la lista de invitados durante la ceremonia de toma de posesión del primer ministro Modi en 2014.

La complicada relación entre ambos países lleva a que China vea a India como un país que podría colaborar potencialmente con sus rivales tradicionales en la zona, como EE.UU., Japón y Australia.

Recientemente, Nueva Delhi modificó algunas normativas para prohibir a las compañías chinas que se apropien de empresas indias en apuros debido a las pérdidas causadas por la pandemia, algo a lo que Pekín se opone.

A pesar de todo ello, China sigue siendo el segundo socio comercial de India. Y, como ocurre con otros socios comerciales, Pekín disfruta de un gran superávit.

Diálogo

En el pasado reciente, las patrullas fronterizas de ambos países han experimentado habitualmente encontronazos, cientos de veces cada año.

En 2013 y 2017, ello llevó a graves crisis que fueron solucionadas tras semanas de maniobras diplomáticas y políticas.

Tras el ultimo gran incidente de 2017, Modi y el presidente chino, Xi Jinping, mantuvieron dos cumbres informales para hablar de sus diferencias.

El encuentro más reciente se llevó a cabo en el Punto de Patrullaje 14 en Galwan, cerca de la zona donde se registraron las víctimas.

Sin duda alguna, este último conflicto agravará la falta de confianza entre ambas naciones, lo que requerirá la intervención política al más alto nivel para evitar que la situación se salga de control.

Why Are India and China Fighting?

The first combat deaths along their border in more than four decades.

In a major setback to recent measures to de-escalate tensions, India and China engaged in a deadly skirmish along their border on Monday night. While details of the clash are still emerging, the incident marks the first combat deaths in the area since 1975.

An Indian Army statement acknowledged the death of an officer and two soldiers, with subsequent reports attributed to officials confirming 17 other soldiers succumbed to injuries—reports that Foreign Policy has not independently verified. Both sides confirm that Chinese soldiers were also killed, but the number is unknown. (China is traditionally reluctant to report casualty figures, and it erases some clashes from official history.) Critically, neither side is reported so far to have fired actual weapons; the deaths may have resulted from fistfights and possibly the use of rocks and iron rods. It’s also possible, given the extreme heights involved—the fighting took place in Ladakh, literally “the land of high passes”—that some of those killed died due to falls.

What is the origin of the conflict?

Despite their early friendship in the 1950s, relations between India and China rapidly degenerated over the unresolved state of their Himalayan border. The border lines, largely set by British surveyors, are unclear and heavily disputed—as was the status of Himalayan kingdoms such as Tibet, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Nepal. That led to a short war in 1962, won by China. China also backs Pakistan in its own disputes with India, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative has stirred Indian fears, especially the so-called China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a collection of large infrastructure projects.

The current border is formally accepted by neither side but simply referred to as the Line of Actual Control. In 2017, an attempt by Chinese engineers to build a new road through disputed territory on the Bhutan-India-China border led to a 73-day standoff on the Doklam Plateau, including fistfights between Chinese and Indian soldiers. Following Doklam, both countries built new military infrastructure along the border. India, for example, constructed roads and bridges to improve its connectivity to the Line of Actual Control, dramatically improving its ability to bring in emergency reinforcements in the event of a skirmish. In early May this year, a huge fistfight along the border led to both sides boosting local units, and there have been numerous light skirmishes—with no deaths—since then. Both sides have accused the other of deliberately crossing the border on numerous occasions. Until Monday’s battle, however, diplomacy seemed to be slowly deescalating the crisis: The two sides had opened high-level diplomatic communications and appeared ready to find convenient off-ramps for each side to maintain face. And both countries’ foreign ministers were scheduled for a virtual meeting next week.

Both countries also have a highly jingoistic media—state-run in China’s case, and mostly private in India’s—that can escalate conflicts and drum up a public mood for a fight. Press jingoism, however, can also open strange opportunities for de-escalation: After an aerial dogfight between India and Pakistan in 2019, media on both sides claimed victory of sorts for their respective countries, allowing their leaders to move on.

Compounding the problems is the physically shifting nature of the border, which represents the world’s longest unmarked boundary line; snowfalls, rockslides, and melting can make it literally impossible to say just where the line is, especially as climate change wreaks havoc in the mountains. It’s quite possible for two patrols to both be convinced they’re on their country’s side of the border.

Has there been similar violence in the past?

There have been no deaths—or shots fired—along the border since an Indian patrol was ambushed by a Chinese one in 1975.There have been no deaths—or shots fired—along the border since an Indian patrol was ambushed by a Chinese one in 1975. But China saw significant clashes with both India and the Soviet Union during the late 1960s, at the height of the Cultural Revolution. In India’s case, that culminated in a brief but bloody clash on the Sikkim-Tibet border, with around hundreds of dead and injured on each side. On the Soviet border, fighting along the Ussuri River saw similar numbers of dead, but tensions escalated far higher than with India, leading to fears of a full-blown war and a possible nuclear exchange that were only alleviated by the highest-level diplomacy. In part, those clashes were driven by political needs on the Chinese side; officers and soldiers alike felt the need to demonstrate their Maoist enthusiasm, leading to such actions as swimming across the river waving Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book.

What could happen next?

India has announced that “both sides” are trying to de-escalate the situation, but it has accused China of deliberately violating the border and reneging on agreements made in recent talks between the two sides. China’s response was more demanding, accusing India of “deliberately initiating physical attacks” in a territory—the Galwan Valley in Ladakh that is claimed by both sides—that has “always been ours.” Army officers are meeting to try to resolve the situation.

While the 2017 Doklam crisis was successfully defused—and was followed by a summit between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Wuhan, China—recent events could easily spiral out of control. If there are indeed a high number of deaths from Monday’s skirmish, pressure to react and exact revenge may build. The coronavirus has produced heightened political uncertainty in China, leading to a newly aggressive form of “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy—named after a Rambo-esque film that was a blockbuster in China but a flop elsewhere. Chinese officials are under considerable pressure to be performatively nationalist; moderation and restraint are becoming increasingly dangerous for careers.

On the Indian side, there is increasing nervousness about how Beijing has encircled the subcontinent. China counts Pakistan as a key ally; it has growing stakes in Sri Lanka and Nepal, two countries that have drifted away from India in recent years; and it has made huge infrastructure investments in Bangladesh. Meanwhile, much has changed since the last time India and China had deadly clashes in the 1960s and ’70s, when the two countries had similarly sized economies; today, China’s GDP is five times that of India, and it spends four times as much on defense.

There will likely be a business impact following the latest clash. Indians, for example, have recently mobilized to boycott Chinese goods, as evidenced by a recent app “Remove China Apps” that briefly topped downloads on India’s Google Play Store before the Silicon Valley giant stepped in to ban the app.

Heightened tensions also put Indians in China at risk. Although numbers are somewhat reduced due to the coronavirus crisis, there is a substantial business and student community in the country. During the Doklam crisis, the Beijing police lightly monitored and made home visits to Indians in the city.

An escalated crisis doesn’t necessarily mean a full-blown war.An escalated crisis doesn’t necessarily mean a full-blown war. It could mean months of skirmishes and angry exchanges along the border, likely with more accidental deaths. But any one of those could explode into a real exchange of fire between the two militaries. The conditions in the Himalayas themselves severely limit military action; it takes up to two weeks for troops to acclimate to the altitude, logistics and provisioning are extremely limited, and air power is severely restrained. (One worrying possibility for more deaths is helicopter crashes, such as the one that killed a Nepalese minister last year.)

In the event of a serious military conflict, most analysts believe the Chinese military would have the advantage. But unlike China, which hasn’t fought a war since its 1979 invasion of Vietnam, India sees regular fighting with Pakistan and has an arguably more experienced military force.

Is there a permanent solution?

China resolved its border squabbles with Russia and other Soviet successor states in the 1990s and 2000s through a serious diplomatic push on both sides and mass exchanges of territory, and they’ve been essentially a nonissue since then. But although the area involved was much larger, the Himalayan territorial disputes are much more sensitive and harder to resolve.

For one thing, control of the heights along the borders gives a military advantage in future conflicts. Resource issues, especially water, are critical: 1.4 billion people depend on water drawn from Himalayan-fed rivers. And unlike the largely bilateral conflicts along the northern border, multiple parties are involved: Nepal, Bhutan, China, Pakistan, and, of course, India. Add on top of that China’s increasing power and nationalism, matched by jingoism on the Indian side, and the prospects of a long-term solution look small. BY JAMES PALMER, RAVI AGRAWAL

(1) (2).jpg)

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.