La travesía de los migrantes venezolanos para escapar del régimen: cruzar a pie el altiplano / The journey of Venezuelan migrants to escape the regime: to cross the highlands on foot

Avanzan por la vía cordillerana al desierto de Atacama, en el norte de Chile, jóvenes de ciudades como Barinas, Maracaibo, Apure y Maturín. Todos sin excepción piden agua. Llevan días, semanas o meses de haber cruzado las fronteras de Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Bolivia

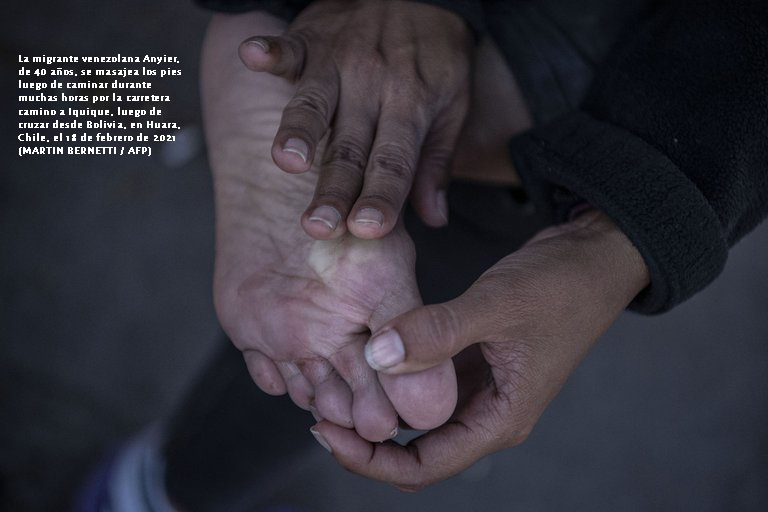

El sol se posa en línea recta en una meseta sin sombra. Con la respiración entrecortada por los 3.700 metros de altura, Anyier intenta reponerse sentada a la orilla de la carretera: hace siete horas cruzó a pie a Chile desde Bolivia, su quinta frontera desde que dejó Venezuela.

“Esto ha sido lo más difícil, horrible”, lanza esta ex empleada de la Siderúrugca Nacional (Sidetur), de 40 años, que el 25 de enero emprendió la travesía de más de 5.000 km junto a Reinaldo, un barbero de 26 años, y la hija de ella Dany, de 14.

Salieron desde Guatire, un suburbio de Caracas, con 350 dólares y una mochila con lo justo.

Como esta familia, muy quemados por el sol y los labios partidos, avanzan por la vía cordillerana al desierto de Atacama -norte de Chile- jóvenes de ciudades venezolanas como Barinas, Maracaibo, Apure y Maturín. Todos sin excepción piden agua. Llevan días, meses o semanas de haber cruzado las fronteras de Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Bolivia.

“Ni agua nos quieren dar”, lamentaba Ramsés, un merideño que tiene como meta llegar donde un amigo en Rancagua -cerca de Santiago-, donde lo esperan para trabajar en un campo agrícola.

Anyier y su familia se detuvieron al borde de la ruta después de 25 kilómetros caminando sin nadie que les ofreciera ayuda en una zona transitada sobre todo por camiones de carga y “últimamente taxistas y esa gente que los extorsiona para llevarlos”.

“Un taxista se paró a preguntarnos si teníamos papeles y cuando dijimos que éramos venezolanos se burló, y aceleró”, contó a la AFP Anyier, dolida hasta las lágrimas.

Tras cruzar muy temprano por el costado del puesto fronterizo cerrado, “nos montamos en una camioneta para que nos trajeran a Iquique o hasta Huara, nos dijeron que no, que no le iban a tender la mano a los venezolanos”, apunta Reinaldo, quien afirma que a migrantes bolivianos y cubanos sí los trasladaron.

Bajo cero

Si de día el sol es insoportable, con ráfagas de viento capaz de mover una camioneta, en la noche “el frío es bajo cero”, indica a la AFP el alcalde de Colchane, Javier García.

En esta comuna de 1.700 habitantes, una de las 10 más pobres de Chile, afirman que han vivido desde enero “un fenómeno migratorio y crisis humanitaria jamás visto en la región”. Cuentan tres muertes oficiales: una mujer colombiana, un bebé y un venezolano de 69 años. “Han muerto de frío, hipotermia”, dice un militar en Colchane.

“Durante meses pudimos apreciar imágenes crudas, inhumanas, que llegaban durante la madrugada a temperaturas bajo cero, -8 o -10, llorando de hambre, a veces sin dinero”, describe el Alcalde, quien también menciona el choque cultural de los migrantes con los aymaras, gente reservada que se siente confrontada a actitudes atrevidas y ruidosas de algunos caminantes.

A unos 40 km de Colchane, un joven de 26 años está paralizado en la carretera, tapado con cobijas viejas, lleva ropa delgada y sandalias de playa con calcetines. Balbucea que se llama Alexander y que viene desde Carúpano, ciudad costera a 500 km de Caracas. Llora porque no siente las manos.

“Es que él no puede con el frío”, aclara su amigo antes de echarse encima de su espalda a darle calor con un abrazo.

“Vamos chamo, pa lante”, le dice. Estáticos, ambos se emocionan, mientras dos amigos más, todos entre 23 y 26 años, echan sus cobijas y mochila al interior de un desagüe al costado de la ruta, a ver si logran protegerse para dormir.

Colchane-Huara

Unos creen que Santiago (a más de 2.000 km al sur de Colchane) está cerca de esa frontera altiplánica que bordea con el pueblo boliviano de Pisiga.

Ahí se enteran de que para llegar a la capital primero hay que ver cómo avanzar a Huara, una localidad 170 km más abajo por esta ruta sin gente a la vista y clima inclemente. Los pocos poblados no tienen luz eléctrica y hay poca agua.

“Muchos llegan con celulares, digo yo ¿cómo no revisan antes adónde van para que tampoco abusen de ellos la gente mala?”, se pregunta Ana Moscoso, dueña de un almacén en Chusmiza.

Son pueblitos tranquilos “y hemos tenido miedo porque algunos entran a las casas sin pedir permiso”, señala Moscoso.

En estas zonas hay caseríos donde el rechazo a los venezolanos creció en enero, como en Quebe, poblado de pastores aymaras de alpacas. Allí cerraron la entrada con un cartel que advierte: “Cuidado – Prohibido ingresar al pueblo – 3 pitbull sueltos”.

Iquique

En Iquique, una ciudad de casi 200.000 habitantes, la pandemia ha golpeado fuerte.

Allí las residencias sanitarias siguen atiborradas de migrantes que deben hacer cuarentena sin poder tramitar ningún estatus migratorio o pedir refugio. A algunos los sacaron de esas residencias a un avión militar para deportarlos en febrero.

Desde antes de diciembre han llegado miles de migrantes a Iquique y más de 8.000 ingresaron por la frontera norte. Algunos tomaron buses hacia el sur de Chile, pero durante la crisis de la primera semana de febrero muchos fueron trasladados desde Colchane a este balneario.

“Pasamos el 31 de diciembre en esta plaza, no tenemos donde ir ni dinero. Hay gente que nos da carpas, nos cocinamos, algunos salen a hacer trabajitos, vender dulces o a pedir dinero”, cuenta Anabella, de 26 años, y con dos niños pequeños que la rodean en la Plaza Brasil de Iquique.

Otros llegaron al final de la cuarentena en la ciudad, como Anyier y su familia. Desde ahí reciben envíos de dinero de amigos o familiares en distintos puntos de Chile y se compran el pasaje en bus a su nueva vida.

“Tengo los nervios de punta”, dijo ella al llegar al terminal de buses Iquique, repleto de inmigrantes venezolanos, colombianos y haitianos, varados por falta de dinero o papeles.

Anyier y su familia lograron llegar a Santiago el 23 de febrero, un mes después de dejar Guatire, y se dirigieron a la casa de su hermana, radicada aquí desde hace tres años. “Gracias a Dios, y ojalá nos vaya bien”, afirma, abrazada a ella.

(Por Paula Bustamante – AFP)

The journey of Venezuelan migrants to escape the regime: to cross the highlands on foot

The sun sets in a straight line on a shadowless plateau. Anyier breathes at an altitude of 3,700 meters and tries to relax on the side of the road: Seven hours ago he crossed Chile on foot from Bolivia, his fifth border since leaving Venezuela.

“That was the hardest, most terrible”This is the start of this 40-year-old former employee of the Siderúrugca Nacional (Sidetur), who on January 25th traveled more than 5,000 km with Reinaldo, a 26-year-old hairdresser, and her 14-year-old daughter Dany.

They left Guatire, a suburb of Caracas, with $ 350 and a backpack with just enough.

Like this family, badly burned by the sun and chapped lips, young people from Venezuelan cities like Barinas, Maracaibo, Apure and Maturín advance along the mountain road to the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. Without exception, they all ask for water. They were days, months, or weeks after crossing the borders of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia.

Under zero

When the sun is unbearable during the day and gusts of wind can move a truck at night “The cold is below zero“, Shows AFP the Mayor of Colchane, Javier García.

In this community with 1,700 inhabitants, one of the 10 poorest in Chile, they confirm that they have been living since January. “a migratory phenomenon and humanitarian crisis never seen in the region”. They count three official deaths: a Colombian woman, a baby and a 69-year-old Venezuelan woman. “”They died of cold and hypothermia”Says a soldier in Colchane.

“For months we could see rough, inhuman images that arrived at temperatures below zero, -8 or -10 at dawn and cried with hunger, sometimes without money,” describes the mayor, who also mentions the cultural shock of migrants with the Aymara. reserved people who are confronted with the daring and loud attitudes of some hikers.

Colchane-Huara

Some believe that Santiago (more than 2,000 km south of Colchane) is near the highland border that borders the Bolivian city of Pisiga.

There they learn that in order to get to the capital one must first see how to get to Huara, a town 170 km further on this route, where no people are in sight and bad weather. The few villages have no electricity and there is little water.

“Many come with cell phones, I say, how can they not check where they are going so that bad people don’t abuse them either?” Asks Ana Moscoso, a shop owner in Chusmiza.

They are quiet little towns “and we were afraid because some would enter the houses without asking for permission”Moscoso points this out.

In these areas there are hamlets where the opposition of Venezuelans increased in January, such as in Quebe, a town of Aymara alpaca shepherds. There they closed the entrance with a sign that warned: “Warning – forbidden to enter the city – 3 pit bulls loose.”

“Here they arrived, they threatened to kill me, to eat me because I took them out of my grandson’s house,” accuses Maximiliana Amaro, 82, who lives on her animals and her crops of quinoa, potatoes and corn.

Angry at the Venezuelans’ transit, Amaro complains that they are entering the city, going into the houses while tending the alpacas and asking for things with arrogance. “And in Colchane they give them everything, food, but not us.”

Hikers in these parts sit on the backs of mining trucks or trucks to move forward. Others pay up to $ 100 per person to be dropped off in the port city of Iquique but are eventually abandoned outside Huara, 78 km northeast of Iquique.

In Huara they are already in the desert, they are seen on the streets, they sleep in the open air and others huddle together in a shed arranged by a villager. Residents, police and military live the situation with astonishment, caution and many empathize with a complex drama. Nobody feels safe, nobody sees an easy solution, everyone asks for help.

Iquique

The pandemic has hit hard in Iquique, a city with almost 200,000 inhabitants.

There, the health residences are still full of migrants who have to be quarantined without being able to process immigration status or apply for refuge. Some were taken from these apartments to a military plane for deportation in February.

Thousands of migrants have arrived in Iquique since prior to December and more than 8,000 have crossed the northern border. Some took buses to southern Chile, but many were moved from Colchane to this resort during the crisis of the first week of February.

“We spent December 31st in this place, we have nowhere to go or money. There are people who give us tents, we cook, some go out to do small jobs, sell sweets or ask for money, ”says Anabella, 26, and with two young children who she in Plaza Brasil in Iquique surrounded.

Others, like Anyier and his family, reached the end of quarantine in the city. From there they receive money transfers from friends or family in different parts of Chile and buy the bus ticket for their new life.

“My nerves are nervous“She said when she arrived at the Iquique bus station, full of Venezuelan, Colombian and Haitian immigrants stranded for lack of money or paper.

Anyier and his family arrived in Santiago on February 23, a month after leaving Guatire, and went to the home of his sister, who has lived there for three years. “”Thank goodness and hopefully we’re fine“She confirms and hugs her.

(By Paula Bustamante – AFP)

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.